How to move a region in Emacs

To move a region horizontally, you can select it, and then press Ctrl-x tab.

After that, you’ll be able to move the selected region with arrows.

To move a region horizontally, you can select it, and then press Ctrl-x tab.

After that, you’ll be able to move the selected region with arrows.

I found a few things that VSCode does better than Sublime Text.

When you create a new file in the sidebar file navigator, VSCode asks for a filename first, and only then opens the file itself. In Sublime Text, after clicking on “New File” context menu item, new tab is opened, and you type a filename only when saving. Creating a file first is better, because in this case your file will have an extension, and proper mode and syntax highlighting will be used when you’ll start writing.

Update: In 2025, Sublime Text has an option to move the sidebar to the right side.

In VSCode, the sidebar can be moved to the right side. This is very useful when you often toggle the sidebar (on small screens, for example) - in this case your code is not shifted to the right side each time the sidebar is shown.

Vocaloid is a music genre where voice is synthesized with a software.

It’s named so because of the Vocaloid software, made by Yamaha, which synthesizes singing voices.

Hatsune Miku, Wikipedia - Hatsune Miku is a character for a voice bank for Vocaloid, released in 2007.

She is very popular, people go to her concerts, there are a lot of fan stuff with her - figures, posters, t-shirts, you name it. She’s not the only one or first virtual voice characters, by the way. MEIKO, for example, was released three years before Miku.

A list of android apps I can recommend.

If you want a simple and elegant android launcher, Olauncher is for you. It removes all icons from the screen and allows you to add just 5 applications to the main screen. These apps are displayed as text - no icons. You can swipe up to see the full list of applications. Also supports swipe customization - for example, you can set left swipe to open contacts, and right to launch the camera.

Markor is a markdown editor with a lot of additional features, such as support for todo.txt format, export to pdf, html and image formats (and yet it’s not all available formats). Todotxt support is great - markor can move completed tasks to the archive file, so your todo.txt will be always clean. The “quick notes” feature is also a great idea - basically it’s just a simple markdown file, but in the app you have a separate button to open it quickly.

DroidFS allows you to create an encrypted container, where you can put all sensitive stuff. Supports wiping imported files from the phone memory.

A good calendar app. Nothing more, nothing less.

The old good foobar music player.

Typescript is a new standard in the Javascript world, and almost all tools and frameworks can deal with it now, but despite that, it’s also true that the existence of transpile step complicates development and hides actual code in a “black box”. In this post, we’ll see how we can write plain javascript code yet use typescript for type checks.

JsDoc is a tool that can generate API documentation from comments that formatted in a specific way, for example:

/**

* Multiply two numbers

*

* @param {number} a - First number

* @param {number} b - Second number

*

* @returns {number}

*/

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

In this example, we have documented a function and its parameters, as well as function and parameters’ types.

Beside simple cases, we can define array types, objects, type unions, export types from other files and packages, and all of that is done inside comment blocks. Following are examples of some JsDoc comments.

A Jsdoc command starts with the /** multi-line comment. Note that comments that don’t start with /** are not treated as JsDoc comments - /*** and /* comments won’t be parsed. Then documentation text goes. When we want to document parameters, we use @param tag:

@param {string} userName User name

@param tag has “{type} parameterName parameterDescription” form. To document return type, @returns tag is used:

@returns {number}

We can make a parameter optional by wrapping it in square brackets:

/**

* @param {string} [name]

*/

function printName(name="Name") {

console.log(name);

}

/**

* @param {*} value

*/

/**

* @param {string} [somebody=John Doe] - Somebody's name.

*/

Here, the id parameter may be string or number:

/**

* Get user by id

* @param {string | number} id User id

*/

function getUser(id) {

//...

}

/**

* @param {number[]} keys - List of keys

*/

We can define our own types with @typedef tag:

/**

* @typedef {Object} User

* @property {number} id - User's id

* @property {string} name - User name

* @property {string} email - User's email

*/

/**

* Get user's info

*

* @param {number} id User id

* @returns {User}

*/

function getUser(id) {

//...

}

As you can see, we can declare a type with the @typedef tag and then use it as if it’s a normal type.

It’s often needed to use a type declared in another file. Taking our previous example, we may want to create a userHelper file, which will contain helper functions that use the User type. Re-defining the User type is a nonsense. Luckily, we can import a type that was defined in another file:

/**

* Returns user's age

*

* @param {import ('./user.js').User} user

* @returns {number}

*/

function getAge(user) {

//...

}

Sometimes we may want to set a type for a variable. In JsDoc, @type tag is used for this purpose:

/**

* @type {import ('./user.js').User}

*/

const user = {

name: "John Doe",

email: "j.doe@email.com"

}

Now typescript will process the object behind the user variable as a User type that was defined in the user.js file.

We can import types from modules as well:

@returns {import("node:child_process").SpawnSyncReturns<Buffer | string | undefined>}

To take an advantage of typescript with JsDoc, we need two things:

// @ts-check comment to the beginning of fileNow, when we run tsc --noEmit command, typescript will check types correctness in all files that have the @ts-check directive.

LSP works fine with this approach, too - you can enjoy hints, autocomplete, error messages and documentation popups right in your text editor (below are screens of Sublime Text with the LSP plugin in action):

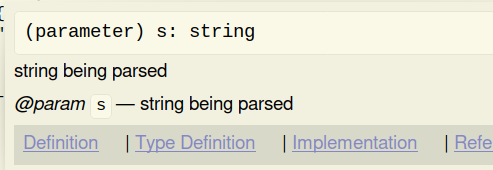

JsDoc popup:

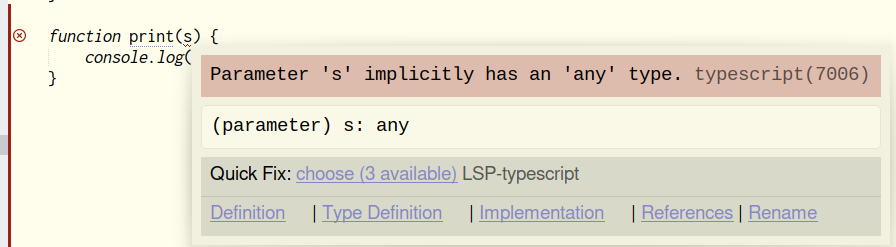

Implict Any type warning:

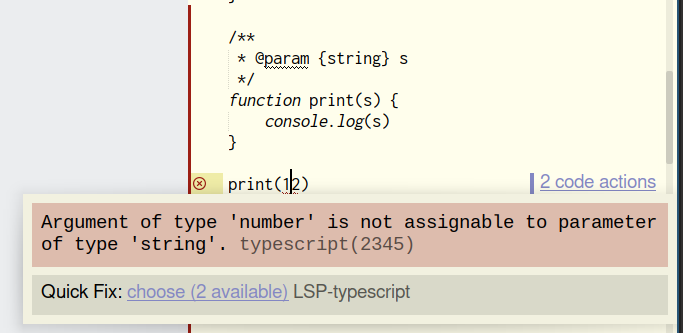

Wrong type error:

Summary: You can use zod library to validate a .env file before building a project. Zod’s capabilities allow to handle very complex cases, though they are very rare.

Have you ever been in a situation when you built your frontend project and found that some value in your .env file was incorrect, or even missed? I’ve been.

After the last time when this happened to me, I decided to add validation to the build step.

zod, dotenv and tsx packages as dev dependenciesnpm i -D zod dotenv tsx

validate-env.ts file in a scripts directory: import 'dotenv/config'

import process from 'node:process'

import { z } from 'zod'

const envSchema = z.object({

VITE_BASE_API: z.string().url()

})

envSchema.parse(process.env)

build script in the package.json:build: "tsx scripts/validate-env.ts && vite build"

In my example I used vite and validated a single variable. You can add as many rules as you need.

Delete the .env file if it exists, and run npm run build. Zod will throw an error, because the VITE_BASE_API variable is not valid:

ZodError: [

{

"code": "invalid_type",

"expected": "string",

"received": "undefined",

"path": [

"VITE_BASE_API"

],

"message": "Required"

}

]

Add the VITE_BASE_API variable to your .env, but leave it empty:

VITE_BASE_API=''

Now zod throws another error, because provided value is not a valid url:

ZodError: [

{

"validation": "url",

"code": "invalid_string",

"message": "Invalid url",

"path": [

"VITE_BASE_API"

]

}

]

When you add such thing to your project, you take additional responsibility for updating validation rules.

I Hope it was useful to someone, good luck.

.env file.ts files in one commandThis post consists from two parts - the first one is a small introduction to the zod library, and the second one is about how we can use it for form validation in Vue.

Zod is a javascript library for data validation. It has pretty small bundle size, works with typescript and javascript, and it’s easy to start with.

Zod is a library for data validation - it doesn’t work with UI elements - only with plain js data. It means that you can use zod on a server side, as well as on a client. It also means that you can’t use it for form validation until form’s input controls are not bounded to a javascript data structure(s).

To validate something with zod, you first need to create a validation schema - a special object that will parse the data.

import {z} from "zod";

const userSchema = z.object({

name: z.string(),

age: z.number()

});

userSchema.parse({name: "Username"});

All fields are required by default. To make some property optional, use optional():

import {z} from "zod";

const userSchema = z.object({

name: z.string(),

age: z.number().optional() // number | undefined

});

userSchema.parse({name: "Username"});

Parse method returns a deep copy of input variable or throws an error if a value doesn’t pass validation. As an alternative, we can use safeParse method, which returns either a copy of input variable or an error. A little remark about return types - in zod, there’s a Input type and a Output type. Usually, they’re the same. But since zod supports data transformation, the output type may differ from the input type.

We can re-use already defined schemas:

import {z} from "zod";

const contactsSchema = z.object({

email: z.string().email(),

phone: z.string().max(50)

});

const userSchema = z.object({

name: z.string().max(50),

contacts: contactsSchema

});

Here, we’ve reused contactsSchema inside userSchema declaration. In general, it’s a good idea to decompose complex schemas into smaller ones - it’s the same thing as creating functions to handle complex logic.

Refinements in zod allow you to create your own validation logic. Documentation is pretty clear on how to use refinements, so I won’t copy examples here.

We will validate a form with personal user information. It will contain these fields:

Email)In this form, the field with work email will be hidden by default, and a “Same as the main email” checkbox will hide/show it. If it’s visible, it’s required. If it’s not visible, it’s not required, because it has the same value as the “Email” field.

First, we need to create a new Vue project:

npm create vue@3

We don’t need any libraries except typescript, so don’t forget to include it in the project during creation.

So, here our starting point - a form with input fields, where each input is bounded to a data model, and a “Submit” button. When a user clicks the button, state of the form is showing up. There’re no any error checks yet, but we’ll add them later.

<script setup lang="ts">

<script setup lang="ts">

import {shallowReactive} from "vue";

interface PersonalInfo {

username?: string;

email?: string;

name?: string;

city?: string;

workEmail?: string;

/**

* True if workEmail is the same as main email

*/

sameEmail: boolean;

}

const formData = shallowReactive<FormData>({

sameEmail: true

})

function onSubmit() {

alert(JSON.stringify(formData, null, 2));

}

</script>

<template>

<div class="container">

<h1>Personal info</h1>

<div class="input">

<label for="username"> Username </label>

<input name="username" v-model="formData.username"/>

</div>

<div class="input" >

<label for="email"> Email </label>

<input name="email" v-model="formData.email"/>

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="name"> Real name </label>

<input name="name" v-model="formData.name"/>

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="city"> City </label>

<input name="city" v-model="formData.city"/>

</div>

<div>

<label for="sameEmail"> Work email is the same as the main </label>

<input type="checkbox" name="sameEmail" v-model="formData.sameEmail" />

</div>

<div v-if="!formData.sameEmail" class="input">

<label for="workemail"> Work email </label>

<input name="workemail" v-model="formData.workEmail"/>

</div>

<button @click="onSubmit"> Submit </button>

</div>

</template>

<style scoped>

.input {

display: flex;

gap: 0.3rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

.container {

display: flex;

gap: 1rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

button {

font-size: 1.5rem;

margin-top: 1.5rem;

background-color: blue;

}

</style>

</script>

<template>

<div class="container">

<h1>Personal info</h1>

<div class="input">

<label for="username"> Username </label>

<input name="username"/>

</div>

<div class="input" >

<label for="email"> Email </label>

<input name="email" />

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="name"> Real name </label>

<input name="name" />

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="city"> City </label>

<input name="city" />

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="workemail"> Work email </label>

<input name="workemail" />

</div>

<button> Submit </button>

</div>

</template>

<style scoped>

.input {

display: flex;

gap: 0.3rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

.container {

display: flex;

gap: 1rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

button {

font-size: 1.5rem;

margin-top: 1.5rem;

background-color: blue;

}

</style>

Now our form looks like this:

And when a user clicks the “Submit” button, we show the value of the formData variable:

Our form now accepts all possible string values, without any restrictions. It’s time to add validation and tell the user what fields were filled are incorrect. Let’s add error messages to the input fields (you can check out input css class in the full source code at the end of the post):

<div class="input">

<label for="city"> City </label>

<input name="city" v-model="formData.city"/>

<div class="error"> city error </div>

</div>

Now each of our fields has an error label:

What we want now is to validate all fields and show corresponding error messages for all invalid fields when a user clicks the “Submit” button. First of all, we need a validation schema:

const personalSchema = z.object({

username: z.string().max(50),

email: z.string().email(),

name: z.string().max(100),

city: z.string().max(100),

sameEmail: z.boolean(),

workEmail: z.string().optional()

}).refine((val) => {

const emailRegex =

/^([A-Z0-9_+-]+\.?)*[A-Z0-9_+-]@([A-Z0-9][A-Z0-9\-]*\.)+[A-Z]{2,}$/i;

return val.sameEmail || emailRegex.test(val.workEmail)

}, {message: "Invalid email", path: ["workEmail"]})

It doesn’t look very simple for such task, though. Let’s take a closer look at what we have here.

username: z.string().max(50),

email: z.string().email(),

name: z.string().max(100),

city: z.string().max(100),

sameEmail: z.boolean(),

These lines describe rules for our fields, and everything is straightforward here.

...

workEmail: z.string().optional()

}).refine((val) => {

const emailRegex =

/^([A-Z0-9_+-]+\.?)*[A-Z0-9_+-]@([A-Z0-9][A-Z0-9\-]*\.)+[A-Z]{2,}$/i;

return val.sameEmail || (val.workEmail ? emailRegex.test(val.workEmail) : false)

}, {message: "Invalid email", path: ["workEmail"]})

This is the root of our schema’s ugliness. The workEmail field is optional when the sameEmail flag is true, and when this flag is false, workEmail should be validated as an email field. In zod, for validations that require a context (and we need one here, because the result of validation relies on another field’s value), the refine() method is used. Its first argument is a function that accepts the whole schema as a parameter, and the truthiness of its result leads to passing the validation. The second parameter is settings - we set the error message and and the error’s path.

This line returns true if the sameFlag is true, or returns the result of email validation, which is done by regular expression. I’ve grabbed this regex from zod’s source code, by the way:

return val.sameEmail || (val.workEmail ? emailRegex.test(val.workEmail) : false)

First of all, we need zod itself:

npm i zod

We want to show error messages only when a user presses the “Submit” button. After that, any changes in input fields should re-launch validation. Also, we need a convenient way to get error messages. First, we need a variable that will hold either the submit button was pressed or not:

const isValidationPerformed = shallowRef(false)

Then, we create a computed variable that returns the list of validation errors:

const errors = computed(() => {

if (!isValidationPerformed.value) {

return undefined;

}

const validationResult = personalSchema.safeParse(formData)

return validationResult.success ? undefined : validationResult.error.format()

})

A few more notes:

We use safeParse because we don’t want to throw errors

We use error.format() to format our errors into a convenient form. This method returns an object with messages in this kind of format:

{

username: {

_errors: ["Required field"]

},

email: {

_errors: ["Invalid email"]

}

city: {

_errors: ["Required field"]

},

}

Inside onSubmit function we set isValidationPerformed to true:

isValidationPerformed.value = true;

And finally, we need to display our error messages. We always display only first error message from the list:

<div class="input">

<label for="username"> Username </label>

<input name="username" v-model="formData.username"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.username?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

We use optional chaining, because we don’t know if the specified field exists in the errors object.

isValidationPerformed is set to false. User can edit any field, and no error messages will be shown.isValidationPerformed variable to true.isValidationPerformed is a reactive dependency in the errors computed, so it’s recalculated when isValidationPerformed has changed.errors has any errors, they’re shown under the input fields.isValidationPerformed is true, any changes in the formData object also trigger errors computed recalculation, so when a user fixes an input value, the corresponding error message is disappeared (again, because of error’s recalculation)If we press the “Submit” button when the form is empty, the “Required” error will be shown under our fields:

When we type something in, for example, the “username” field, the error under the input field is disappeared:

But if we clear the field, no any error message will be shown:

That’s because now our formData.username contains an empty string, not an undefined value, and this situation fully satisfies the validation condition (it’s a string and its length don’t overflow the limit). If we want to forbid empty and space-only strings, we may use trim() and min() combination:

// Create a separate zod schema for non-empty strings

const nonEmptyString = z.string().trim().min(1);

const personalSchema = z.object({

username: nonEmptyString.max(50),

email: nonEmptyString.email(),

name: nonEmptyString.max(100),

city: nonEmptyString.max(100),

sameEmail: z.boolean(),

workEmail: nonEmptyString.optional()

}).

refine((val) => {

const emailRegex =

/^([A-Z0-9_+-]+\.?)*[A-Z0-9_+-]@([A-Z0-9][A-Z0-9\-]*\.)+[A-Z]{2,}$/i;

return val.sameEmail || emailRegex.test(val.workEmail)

}, {message: "Invalid email", path: ["workEmail"]})

Now everything works fine:

<script setup lang="ts">

import {shallowReactive, shallowRef, computed} from "vue";

import {z} from "zod";

export interface PersonalInfo {

username?: string;

email?: string;

name?: string;

city?: string;

workEmail?: string;

/**

* True if workEmail is the same as main email

*/

sameEmail: boolean;

}

const nonEmptyString = z.string().trim().min(1);

const personalSchema = z.object({

username: nonEmptyString.max(50),

email: nonEmptyString.email(),

name: nonEmptyString.max(100),

city: nonEmptyString.max(100),

sameEmail: z.boolean(),

workEmail: nonEmptyString.optional()

}).

refine((val) => {

const emailRegex =

/^([A-Z0-9_+-]+\.?)*[A-Z0-9_+-]@([A-Z0-9][A-Z0-9\-]*\.)+[A-Z]{2,}$/i;

return val.sameEmail || (val.workEmail ? emailRegex.test(val.workEmail) : false)

}, {message: "Invalid email", path: ["workEmail"]})

const isValidationPerformed = shallowRef(false)

const formData = shallowReactive<PersonalInfo>({

sameEmail: true

})

const errors = computed(() => {

if (!isValidationPerformed.value) {

return undefined;

}

const validationResult = personalSchema.safeParse(formData)

return validationResult.success ? undefined : validationResult.error.format()

})

function onSubmit() {

isValidationPerformed.value = true;

if (!errors.value) {

alert(JSON.stringify(formData, null, 2));

alert("All good!")

} else {

alert(JSON.stringify(errors.value, null, 2))

}

}

</script>

<template>

<div class="container">

<h1>Personal info</h1>

<div class="input">

<label for="username"> Username </label>

<input name="username" v-model="formData.username"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.username?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

<div class="input" >

<label for="email"> Email </label>

<input name="email" v-model="formData.email"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.email?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="name"> Real name </label>

<input name="name" v-model="formData.name"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.name?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

<div class="input">

<label for="city"> City </label>

<input name="city" v-model="formData.city"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.city?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

<div>

<label for="sameEmail"> Work email is the same as the main </label>

<input type="checkbox" name="sameEmail" v-model="formData.sameEmail" />

</div>

<div v-if="!formData.sameEmail" class="input">

<label for="workemail"> Work email </label>

<input name="workemail" v-model="formData.workEmail"/>

<div class="error"> {{errors?.workEmail?._errors[0]}} </div>

</div>

<button @click="onSubmit"> Submit </button>

</div>

</template>

<style scoped>

.input {

display: flex;

gap: 0.3rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

.container {

display: flex;

gap: 1rem;

flex-direction: column;

}

button {

font-size: 1.5rem;

margin-top: 1.5rem;

background-color: blue;

}

.error {

margin-top: -0.5rem;

color: red;

font-size: 0.5rem;

}

</style>

In our example, we declared our form interface first, but it’s also possible to infer the whole type from a zod schema:

type PersonalInfo = z.infer<typeof personalSchema>;

There’re also:

yup over zod is the when() method, with which you can create conditional validation. By the way, vee-validate uses yup by default as a validation engine.In this post I’ll tell about my experience with Workflowy - famous outliner service, which I’ve been using for half a year at the moment of writing.

I don’t suffer from information gathering much, but I have pretty minimal needs - sync bookmarks, keep some text notes and todo items. I used to keep bookmarks with Firefox sync mechanism and my text notes/todo items with the help of protectedtext (which is a great service!). But because firefox became unusable, I switched a browser from Firefox to Vivaldi on a smartphone, while on a laptop I was still using firefox. That broke my bookmarks workflow, and at that moment I had two bookmark lists, and each of them was living its own life. What about notes? - I was happy with how I dealt with them, but it changed over time because of bad usability on a smartphone. I tried a lot of note management tools (Trello, TickTick, Notion, Org mode, Simplenote, Standardnotes, Google Keep), but finally I’ve picked Workflowy. The main reason was that I thought that I would be able to adopt it for all my needs (And strictly speaking, I succeed at this). I was using it for less than a month before I bought PRO subscription. Now the story begins…

Workflowy has a great UI. It’s clean and consistent, what else do I need? In general, nothing. There are some issues with the mobile app - I’ll list them in the next section.

Here, it’s worth mentioning DynaList - a clone of Workflowy, which in my opinion has a terrible user interface:

This is a list of my issues with the mobile interface:

Everything else is very nice.

I had been using only mouse for the first few months, but when I tried to use a keyboard, I was thrilled. Now, on desktop/web platform, about half of my actions are done with a keyboard. You can always toggle the help panel with shortcuts in three steps:

My day to day shortcuts are:

Ctrl - arrow up/arrow down - Expand/collapse a nodeAlt - arrow left/arrow right - Zoom out/zoom inCtrl - Alt - m - Move a nodeCtrl - Enter - Mark a node as completedCtrl - Shift - Backspace - delete a nodeShift - Enter - Add a new nodeOn a smartphone, the application starts very slow. I hate it when I take the smartphone to write out a quick note and have to wait more than 5 seconds for application to be loaded. Any default note taking application starts in a moment on any android device, and such slow Workflowy’s start speed is very irritating. I’m not the only one who have faced with this - there’s a ticket with this problem. The support says that 10-15 seconds for startup is “expecting” and “pretty standard for now”.

In the march of 2023, Workflowy announced “Significant speed improvements” of load time - now it’s 40% less in average. However, I personally haven’t noticed any speed improvements - maybe this is because I have a very small amount of list items, while they seem like they have boosted load time only for accounts with a large number of nodes, I don’t know.

Workflowy is an outliner. It’s poorly suited for rich content with images, paragraphs, tables etc. With this service, you should consider every node as one single, atomic block of the whole text. Do you want to insert an image? Create a node. Need a list? Create a node for each item. Want to split some notes into paragraphs? You know what to do. And this way of working with documents may be unacceptable for people who want to use Workflowy for writing long text and complex documents.

They’re selling it as the feature that would incline Trello users to make a switch to Workflowy.

I think this is silly. Trello sucks, but if someone uses it, Workflowy’s unintuitive kanban implementation will just enhance his attachment to Trello.

In summary, I like Workflowy, but I’m afraid that the team will be adding more and more features to it in pursuit of new users, and as a result, Workflowy will become everything, and nothing. Will I renew my subscription? Definitely not - I don’t use it heavily enough to pay for it.

The point of article: keep components in one single directory with a flat structure.

Almost all Vue projects have a components directory, where all application’s components are kept. There are plenty of ways how you can organize them, but I think it’s better to put all your components right into components directory and do not create any sub-directories trying to make the structure obvious and simple. It may sounds strange, but in practice exactly this way is more simple and future-proof.

As was told, the flat structure implies that components’ directory have no any sub-directories, just component files. Besides the components themselves, this directory contains their tests, if any. This way of organizing components has some benefits over non-flat structure:

It’s easier to see the whole picture

Imports are shorter:

import Avatar from "./Avatar.vue"

No ugly paths, like this:

import Avatar from "@/components/main/header/Avatar.vue"

import TextLabel from "../../Text/TextLabel.vue"

You won’t spend your time deciding where should you put your new component. This is a really good one. If you have a card with an article author’s avatar and a header with the same avatar, where should you put the “Avatar.vue”? In a “header” subdirectory or in a “card”? Or maybe create a “shared” directory and put all repetitive components here? It’s hard to decide actually. Moreover, often, when we create a new component, we don’t know whether it will be used somewhere else or not. With the flat structure, it’s not an issue.

Such structure forces you to re-use your components. If you group components into different directories based on their functionality, business logic or visual hierarchy, then you wouldn’t try to check whether a similar component already exists or not, or at least if you do, it will be hard to explore it.

Resistance to changes. no more need to move component between directories and globally rename it because now it’s not in the TodoList but in Shared directory.

Applying official components’ naming convention dramatically increase understanding of what’s going on with your components. Consider this list of components:

Button.vue

MainLogoutButton.vue

LogoutButton.vue

Checkbox.vue

TextInput.vue

Sidebar.vue

Header.vue

AppButton.vue

AppTextInput.vue

AppCheckbox.vue

LogoutButton.vue

TheLogoutButton.vue

TheSidebar.vue

TheHeader.vue

At first glance it looks like there’s no differences and both lists provide the same information, but these styles of naming are very different. Let’s take MainLogoutButton.vue and LogoutButton.vue from the first example. What’s the difference between them? Most probably we need to check their sources, because just their names don’t tell us anything. But in the second example, we know that the TheLogoutButton.vue is the component that is instantiated only once per page, or even the whole application, and most probably it has some specific application logic that don’t allow to re-use this component, though it’s not a requirement.

The App prefix from the second example also tells us that those components don’t use any shared application state or implement any logic (such components are often called “dumb”) - they’re used only for visual representation.

It’s very common to use pages (views) that represent whole pages of the application, and layouts directory with components that control high-order visual hierarchy ( for example, in a Profile layout we should always see TheHeader component at the top of the page, but in the Dashboard layout it shouldn’t be presented). Some frameworks (Nuxt) or plugins for vue (unplugin-vue-router, vite-plugin-pages) expect those directories, so if you use them, it’s ok to move such kind of components outside the components directory, just keep track of these directories cleanliness - they shouldn’t contain non-page or non-layout components.

Ctrl - n - create new tabCtrl - w - close current tabCtrl - tab - move to the next tabIf you don’t know hotkeys for a command, or don’t know if such a command even exists, use command palette. It’s the first place where you should search for unknown commands. To open the command palette, press Ctrl - Shift - p, and then type command name. For example, you want to transform selected text to upper case. This is what you should do:

Ctrl - Shift - p

Enter (or click )Ctrl - 0 - focus on sidebarCtrl-k, Ctrl-b - toggle sidebarSublime Text allows you to open a few tabs side by side.

Alt - Shift - 1 - leave only one edit bufferAlt - Shift - 2 - split window vertically ( 2 tabs )Alt - Shift - 3 - split window vertically by (3 tabs)Alt - Shift - 4 - split window vertically by (4 tabs)Alt - Shift - 5 - “Grid layout”. Two windows in a rowAlt - Shift - 8 - Split horizontally, 2 tabsAlt - Shift - 9 - Split horizontally, 3 tabsYou can move between layout windows with Ctrl + <number> hotkeys. Ctrl - 0 - move to the sidebar, Ctrl - 1 - move to the first tab, Ctrl - 2 - move to the second tab, and so on.

Ctrl - Shift - arrow up/arrow down - move the current line up/downCtrl - c - copy the whole lineCtrl - x - cut the whole lineCtrl - Shift - arrow up/down - move the line up/downFirst, you need to install package control. It’s the Sublime Text package manager.

Ctrl - Shift - p)Sublime Text has a great support for working with multiple cursors. To set an additional cursor, use Ctrl - click. Then, all commands ( like moving cursor, char/word deletion etc) will be applied to all cursors.

There’s also nice feature in Sublime Text - you can select next occurance of the current word. It works this way:

Ctrl - d on current word. It will be selected.Ctrl - d one more time. The next occurance of this word will be selected.This is useful when you want, for example, delete or replace some occurances of a word.

These commands may be useful for programmers.

Ctrl - m - move between brackets. Works even if the cursor is placed in the middle of text between them.Ctrl - Shift - m - select text between bracketsCtrl - g - go to lineCtrl - ; - open dialog with all words in the current document. Start typing, then select required word with Enter. Then you can move to the next occurance of the word with F3